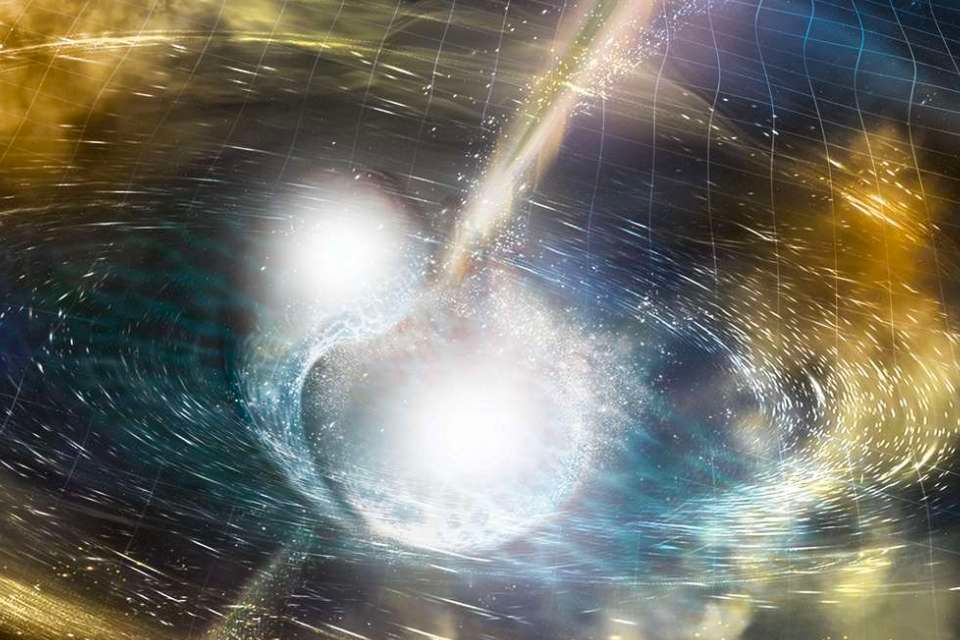

Including possibly – for the first time – a collision between a black hole and a neutron star.

It was world news in 2016 when researchers announced that they had first detected gravitational waves a year earlier. A new field of research was born and in the years that followed scientists were able to regularly report new discoveries; often it involved gravitational waves caused by colliding or merging black holes, but a few years ago there were also gravitational waves from merging neutron stars detected.

Upgrade

For example, the aftereffects of eleven mergers were detected between 2015 and 2019. A wonderful result. But there was a lot more to it, researchers promised when they switched off the gravitational wave detectors in 2018 to then to provide them with a new upgrade and thus make them even more sensitive. And the researchers have kept their word, as it appears now that they announce this week that they have discovered the gravitational waves of 39 (!) New mergers.

Half a year

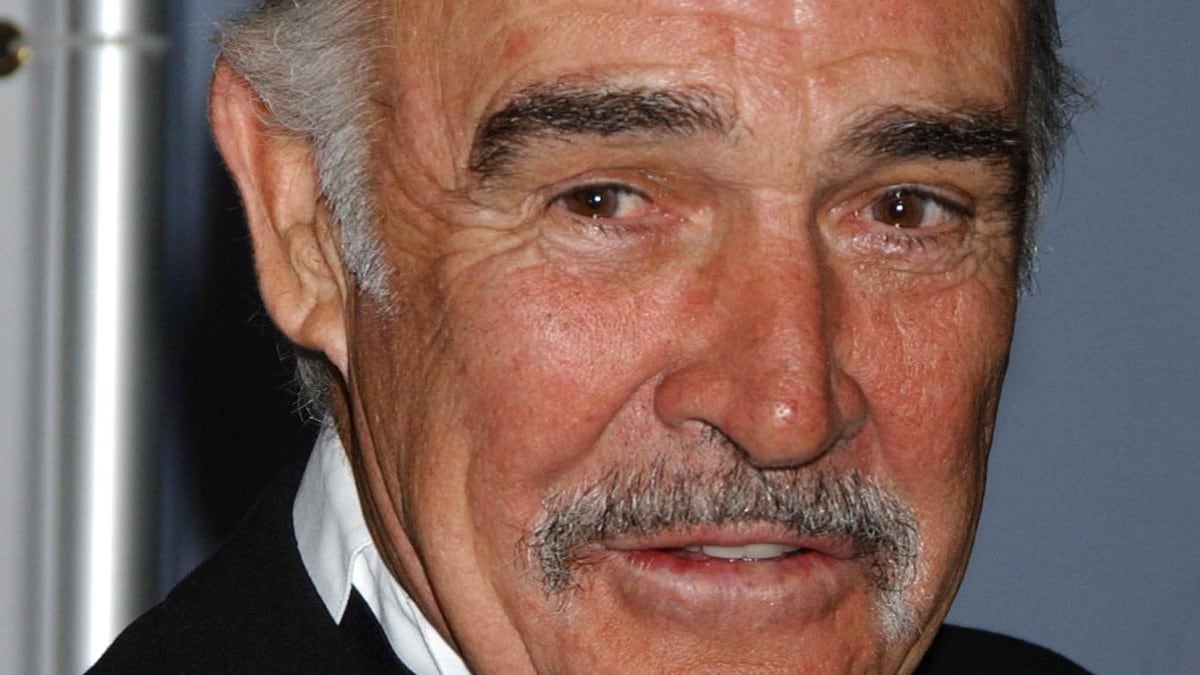

After being upgraded, both the gravitational wave detectors in the US (LIGO) and the detectors in Italy (Virgo) went back to work in April 2019. And the gravitational waves of the 39 collisions announced this week were detected between April 1, 2019 and October 1, 2019 – in half a year. “That’s more than one discovery a week,” emphasizes researcher Andrew Williamson.

Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime. You can best imagine this space as a tightly stretched sheet. Planets and stars lie on this ‘cloth’ like marbles, causing spacetime to be curved locally. In addition, waves also travel through spacetime. These are gravitational waves and they arise when two heavy objects rotate or merge very close to each other. Observing gravitational waves is not that easy yet, but it is possible with so-called interferometers, as the researchers have repeatedly demonstrated in recent years. The LIGO-Virgo Collaboration works with interferometers in the US and Italy. In these interferometers, a laser beam is emitted that is split into two perpendicular arms that are four kilometers long. At the end of those arms we find a mirror that reflects the laser beam. When the two arms are exactly the same length, the reflected laser beams will cancel each other out. However, it becomes different if one arm becomes slightly longer than the other due to the passage of a gravitational wave (see the video below).

–

Most of the gravitational waves the researchers captured in 2019 were caused by colliding black holes. But there is also a collision between two neutron stars between. And possibly also a collision between a black hole and a neutron star. The latter would be a first.

“In conjunction with the 11 discoveries made for 2019, we have now discovered 50 gravitational wave events and there are bound to be many more to come,” said Williamson. Because LIGO and Virgo will soon start a new observation run. In addition, work is currently underway on a detector called LISA – which should detect gravitational waves from space sometime after 2034.

And so this fairly new research field is constantly evolving. And that’s a good thing, because there is still so much to discover. For example, researchers hope to use the gravitational waves of colliding black holes to clarify what a typical black hole looks like, how many black holes there are and how the black hole population has changed as the universe evolved. Meanwhile, the collisions between neutron stars can provide more insight into the internal structure of these still quite mysterious stars and provide even more clarity about the speed at which the universe is expanding. Chris van den Broeck, affiliated with the National Institute for Subatomic Physics (Nikhef) and member of the LIGO-Virgo Collaboration, explained earlier. And finally, things will undoubtedly also be discovered and mysteries unraveled that we cannot really imagine yet. “There may be some surprises to come,” Williamson confirms.

POPULAR ON SCIENTIAS.NL

Keep amazed ✨

Receive the most beautiful space photos and interesting popular science articles every Friday. Get the free Scientias Magazine together with 50,000 others.

–