Brahim Benaicha dreamed of this country where the “we wash ourselves with perfume“and eats with a small spoon. When this son of an Algerian caravanner landed in November 1960, at the age of eight, in the “slush” of the slums of Nanterre, “it was the big disappointment“.

“It was more than a pigsty, we lived with the rats“at the gates of Paris, he summarizes. But it was his childhood and it was also “happy“. The mood was “solidarity” in this “village“with walls imprinted with a”preserved culture“, he recalls, far from the images of “urban leprosy“often associated with what served as a habitat for thousands of people until the 1970s.

At the end of the Second World War, France was in full reconstruction and labor flowed in, in particular from the colonies of the Maghreb and Portugal. Brahim Benaïcha’s father left the desert for the Citroën factories, quai de Javel, in the west of Paris, and, for lack of sufficient housing, the family settled in one of these hastily built slums from the years 1950, with wood, concrete blocks and other materials salvaged from building sites.

Those of Nanterre had more than 10,000 inhabitants and became the symbol of the relegation of North Africans, mediatized when hundreds of Algerians left to demonstrate in the capital on October 17, 1961 at the call of the National Liberation Front.

Brahim Benaïcha lives on rue des Pâquerettes, a dwelling wedged between brand new HLMs with salmon pink facades – “le Grail“for the child of then, and wastelands, these”gardens“where the football games are endless. A few meters away, the public school where he rubs shoulders”the well-cleaned little Frenchies“.

A medina

The conditions are “more than sketchy“, the small size and the impossible intimacy as the partitions are thin. At the slightest rain, the paint fades, “everything was leaking” and “it was patched up with sheets of tar“. Most “memory softens violence“, slips Mr. Benaïcha. And more than water chores in the middle of winter, he keeps in mind the cultural or sports outings offered by students from the nearby university.

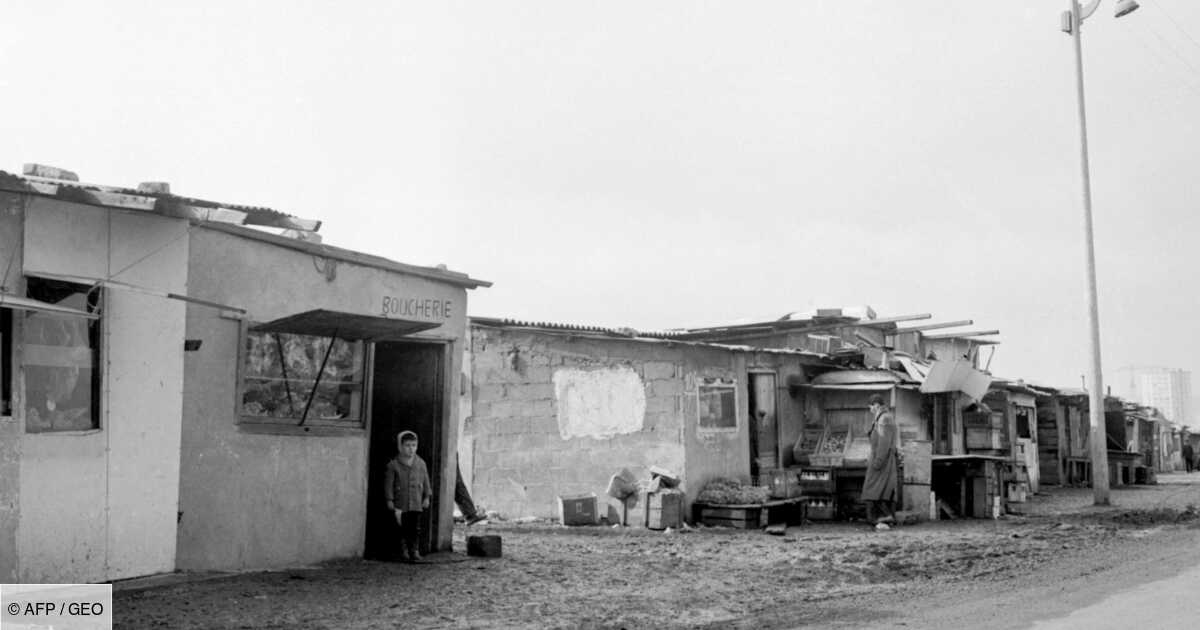

He still hears the “brouhaha“from the slum,”its grocery store, butcher and two cafes” or “it was playing dominoes“. And still visualize the sheep running in the narrow alleys at the time of Eid. Nicknamed the “Little Nanterre”, the makeshift village is anything but disorganized.

“It was thought that the Arabs lived in deplorable conditions because they came from the countryside“, says Serge Santelli, architect and author of a book on the shantytown of the rue des Près in Nanterre which bordered the Seine.

However, despite their limited means, they manage to shape a real “village agglomeration“built on”same configurations as traditional Maghrebian historic medinas and towns“.

“It is a very compact urban architecture, without public space. In the structuring of space, these are not barracks. These are houses made up in a very repetitive way, we have a typology of house. It is not a coincidence (…)“, analyzes M. Santelli.

Home is there”traditional“, organized around a courtyard.”It is a sequence of living rooms that we cross“, describes Mr. Santelli.

“transit cities”

The large urban projects in Nanterre put an end to these slums. From “transit cities” sprang up from the ground in no man’s land.

“It was necessary to ‘civilize’ the North Africans and ‘improve’ their way of life in these cities whose plan resembles that of the Grands ensembles“, these collective dwellings built in France from the mid-1950s. However, the objective was “not only to house the Arabs but also to teach them what modern housing is“, explains Serge Santelli.

In 1970, “it was extremely violent to be forced to move overnight in a transit city“, recalls Mr. Benaïcha who loses the warmth of this neighborhood for towers where the population will be marginalized. And “it was a heartbreak to leave the slum“, finally destroyed two years later.

Read also :

Algerian war: the children of harkis, between omerta and a feeling of shame

– –

From French colonization in Algeria to independence: a look back at 132 years of struggle

– –

“From beautiful dawn to sad evening”: the true novel of Algeria

– –

–