About the silencing of the BBC

Mitko Grigorov answers, he says

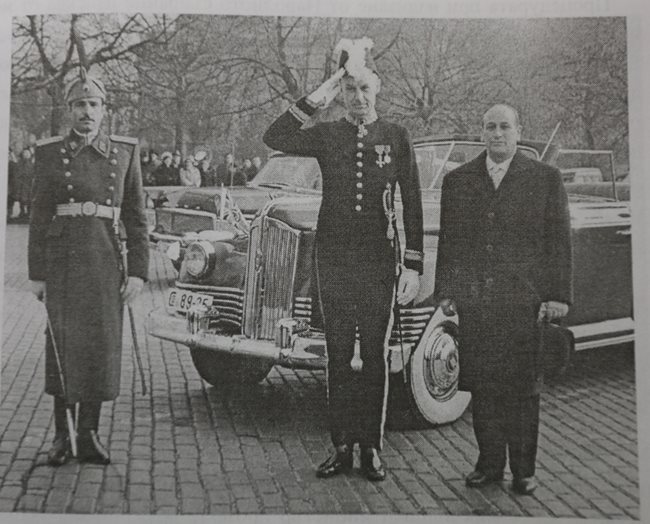

Ambassador William Harpup before the National Assembly before handing over his credentials. The photos are from the book “Soviet Bulgaria (1964-1966)”

–

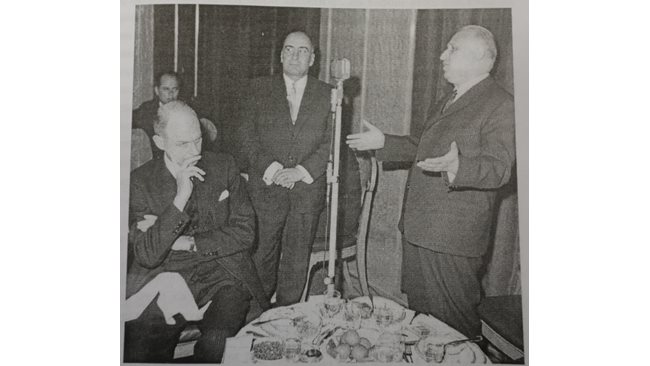

Todor Zhivkov at the reception

On January 17, 1964, Ambassador William Harpam presented his credentials to the Deputy Speaker of the National Assembly, Georgi Kulishev.

The then Speaker of Parliament, Dimitar Ganev, was seriously ill and rarely appeared in public. He died only three months later, on April 20, 1964.

Although there have been diplomatic relations between Bulgaria and Britain for 83 years, Harpam is the first British ambassador to Sofia. Until then, they were at the mission level.

In the letters that the British diplomat handed to Kulishev, Queen Elizabeth II informed the Presidium of the National Assembly of Bulgaria about the recall of Anthony Lincoln and the accreditation of William Harpamp as Her Majesty’s Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Bulgaria.

The British

freezes hard

during

the ceremony

The temperature is well below zero, but accompanied by the head of the protocol Danchev, he travels from the embassy to the National Assembly in an open car. The instruments of the honorary company freeze from the cold and the musicians barely play the anthems of Bulgaria and Great Britain. The ceremony was attended by Foreign Minister Ivan Bashev and member of the Presidium of the National Assembly Prof. Rada Balevska.

On February 11, Prime Minister Todor Zhivkov, who is also the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, invited the British ambassador to a reception for the heads of diplomatic missions, organized at the Vrana residence.

The hosts are Foreign Minister Ivan Bashev and his wife. Todor Zhivkov appears with his wife Mara Maleeva – Zhivkova.

The ambassadors of the United States and Great Britain and their wives are invited to sit at Zhivkov’s table. Bashevi is also housed there, as is the Polish ambassador, who is the doyen of the diplomatic corps. The Soviet ambassador was not present at the reception, he had left for Moscow.

However, this arrangement is during the concert of several famous Bulgarian singers and musicians. Then, in another room, where the “bite and beer” is, Zhivkov sits in the chair of the table, on his left is the Polish ambassador, and on the right is William Harper. His wife is at a separate table with Mara Maleeva.

Mitko Grigorov is also sitting at Zhivkov’s table. In his report to the Foreign Office, Harpham introduced him as a minister without portfolio and head of the party-government commission for ideological and cultural issues. In fact, in addition to being a minister, Grigorov is the secretary of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party on ideological issues. Zhivkov speaks mainly at the table, the others mostly nod their heads.

At some point it was about the BBC broadcasts and the ambassador asked when Bulgaria would stop jamming the radio. Zhivkov escapes with the fat joke that Mitko Grigorov is responsible for the jamming.

Todor Zhivkov will often use jokes of this type over the years. For example, he said that he was responsible for Bulgaria’s successes and that Stanko Todorov was to blame for his failures.

At the reception, Zhivkov delivered a long speech in which he preached the virtues of communism and peaceful coexistence. His speech ended with a toast, thanks to which diplomats saved the applause. After the Bulgarian Prime Minister sat down, William Harper told him that his speech was good, but he could not agree with everything said in it. But the Polish ambassador gave a long eulogy.

In his reception report, Ambassador Harper wrote that “Zhivkov, who radiated artificial cordiality, wanted to somehow submit the olive branch to Western missions.”

After three months in Bulgaria, the ambassador sent a report to the Foreign Office on his first impressions of Bulgaria.

He begins with a curious but inaccurate comparison: “When I learned that I was leaving Paris for Sofia, I remembered how Voltaire’s Candide was banished from his earthly paradise and found himself in the barbaric land of the Bulgarians, where he experienced many hardships before succeeding. to escape and continue his adventures elsewhere … ”

What is she

the truth though?

When Voltaire published his short story Candide or Optimism in 1759, the Age of Enlightenment was in full swing. In two successive chapters, Voltaire speaks of the Bulgarians, calling them terrible and strong. They fight the Avars and harass the main character Candide.

In the novel, the Bulgarians put shackles on Candide’s legs and make him turn right, left, raise his rifle, lower his rifle, measure himself, shoot, run, and after all hit him with thirty sticks.

The next day he does the exercises not so badly and gets twenty sticks, on the third day only ten sticks are hit and everyone looks at him as a miracle.

Those who have read this short story know very well that by the name “Bulgarians” the author actually means the Prussians, and the Avars are the French. The king of the Bulgarians was the Prussian King Frederick II, with whom Voltaire had bad relations.

Perhaps influenced by Voltaire, the ambassador wrote in the report: “The Bulgarian people are not a very attractive race.

They are Bulgarians

managed by

mode whose

credo we

we despise

(…) The average Bulgarian does not feel particularly warm feelings towards us. ”

In 1995, William Harpum was interviewed by Bulgarian journalist Dimitar Dimitrov. Before him, the diplomat admits that he soon regretted his decision for the Bulgarians. He even asked Dimitrov not to quote the excerpt from the report in question.

“He knew very well that, unlike totalitarian regimes and George Orwell’s 1984 novel, the archives remain authentic,” the Bulgarian journalist said. William Harpum died just three months before the interview was published. The impressions of the British ambassador about our capital are curious and almost 100% true.

“The city of Sofia is gray and depressing in winter and especially when one leaves the center, the houses are either dilapidated, or if they are new, they are built to lower standards. But much of the grayness goes away with the end of winter. Dirty snow disappears from the sidewalks and well-arranged trees in the streets bloom. Besides, in less than half an hour you can find yourself in an area that looks like Switzerland … ”

According to Harpham, with the development of industry and bureaucracy between 1946 and 1961, Sofia more than doubled. The first ambassador of London in Sofia also raised an issue, which was commented on and discussed several times in the Foreign Office.

Is it worth Britain to make the necessary patient effort to improve its relations with Bulgaria?

How important from the British point of view is the small Balkan country with a population approximately as large as the population of London.

For the Foreign Office, Bulgaria is low on the list of British priorities. It is the least important of the countries of the Soviet bloc and

hers

it is a government

the most submissive

before the dictates of

Moscow

and at the same time the most illiberal … William Harpup came to the same arguments as the diplomats who served in the English legation before him. “Our presence here is necessary to encourage those Bulgarians who think like us,” Harper wrote. “We must show them by our example and in all possible ways that a freer way of life can still be found and that we have not forgotten them in their current difficult situation …”

Beginning with Voltaire, Ambassador Harper concludes his first report to London with Cervantes.

The finale sounds very personal and emotional: “It will probably sound quixotic if I say that the life of this infamous capital fills me with great compassion for a nation that, throughout its history, seems to have never received justice. Therefore, despite the refusals and disappointments I receive, I propose that we continue to help Bulgarians achieve improvements in their moral and material living conditions. “

–